Every year, millions of unused or expired pills end up in toilets and sinks across the UK and beyond. People do it because it’s easy, because they think it’s safe, or because they’ve never been told otherwise. But flushing medications isn’t just a harmless habit-it’s a quiet environmental crisis playing out in rivers, groundwater, and even your drinking water.

What Happens When You Flush a Pill?

When you flush a pill, it doesn’t disappear. It enters the sewage system, where most wastewater treatment plants aren’t designed to remove it. These plants were built to filter out solids, bacteria, and nutrients-not tiny chemical molecules like ibuprofen, antidepressants, or antibiotics. Studies show that up to 80% of rivers and streams in the U.S. contain traces of pharmaceuticals, and the same pattern is now being seen in UK waterways. The UK Environment Agency has detected over 50 different drugs in rivers, including painkillers, beta-blockers, and even hormones from birth control pills. These aren’t random findings. In 2002, the U.S. Geological Survey found pharmaceuticals in 80% of the waterways they tested. Since then, detection methods have gotten better, and the list of drugs found keeps growing. In some cases, concentrations are low-nanograms per litre-but that’s enough to cause harm. Fish in polluted rivers have been found with altered sex organs, reduced fertility, and abnormal behaviour due to exposure to estrogen-like compounds from birth control pills. Antibiotics in water contribute to the rise of drug-resistant bacteria, a growing global health threat.Why Your Medicine Cabinet Is a Hidden Polluter

The average household in the UK holds onto at least 10 unused or expired medications. Many people keep them because they’re afraid of wasting money, or they think they might need them later. Others simply don’t know what to do with them. A 2021 FDA survey found only 30% of Americans knew about take-back programs. In the UK, awareness is similarly low. The problem isn’t just flushing. Throwing pills in the trash is just as bad. Landfills leak. Rainwater washes through waste, picking up chemicals and carrying them into soil and groundwater. One study found acetaminophen concentrations in landfill leachate as high as 117,000 nanograms per litre-far beyond what any wastewater plant can handle. Even if you mix pills with coffee grounds or cat litter before tossing them, they’re still in the landfill, still at risk of leaching out.The FDA’s ‘Flush List’-What’s Really Safe?

You might have heard that some medications are safe to flush. That’s true-but only for a very short list. The FDA maintains a ‘flush list’ of drugs that pose a high risk of accidental overdose or misuse if left in homes. These are mostly powerful opioids like fentanyl patches, oxycodone, and methadone. For these, the risk of someone-especially a child or pet-accidentally ingesting them outweighs the environmental risk of flushing. But here’s the catch: this list includes only about 15 medications out of thousands. For everything else-your blood pressure pills, your antibiotics, your painkillers-flushing is not recommended. And yet, many people still do it, confused by mixed messages. The FDA updated this list in October 2022, removing two drugs and adding three more opioids. It’s not a blanket permission to flush anything. It’s a targeted exception for high-risk drugs.

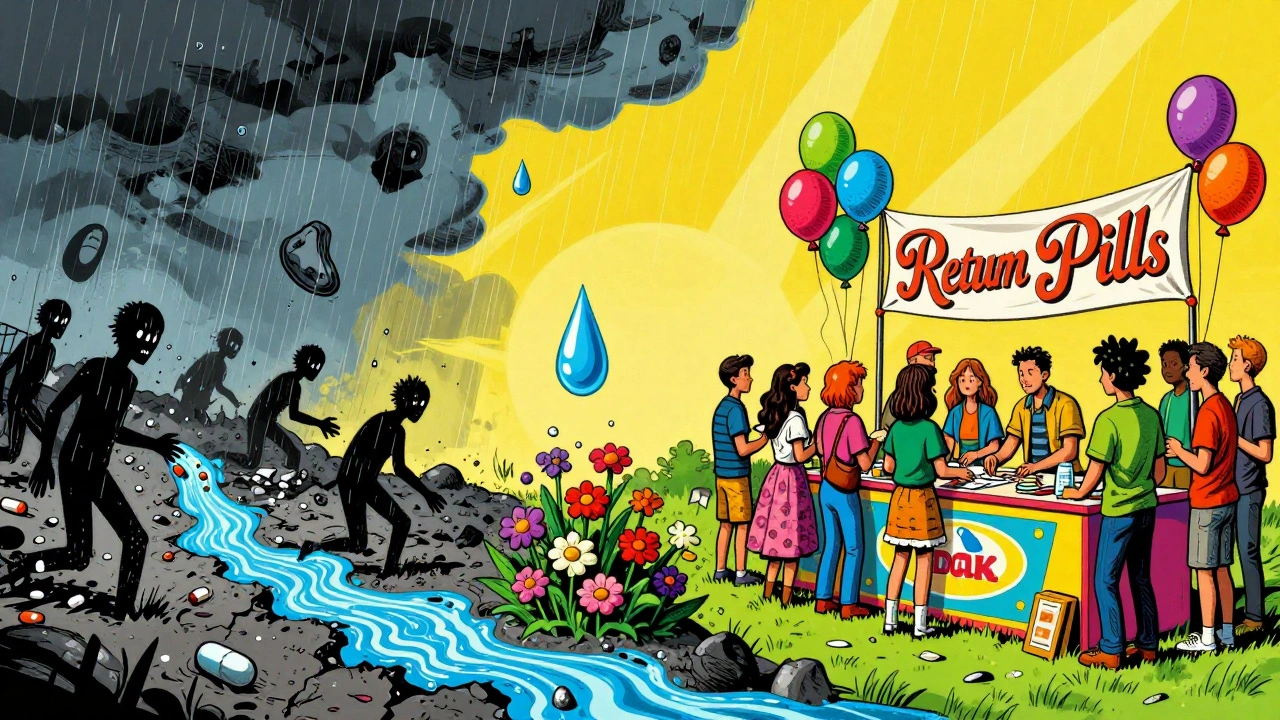

The Best Alternative: Take-Back Programs

The cleanest, safest way to dispose of unused medications is through a take-back program. These are drop-off locations at pharmacies, hospitals, or police stations where you can hand over old pills, patches, or liquids without cost or questions asked. In the UK, many pharmacies participate in the National Health Service’s medication return scheme. In England and Wales, you can ask your local pharmacist if they accept unwanted medicines. Some local councils also run seasonal collection events. Take-back programs prevent drugs from entering water or landfills entirely. They’re collected and incinerated under controlled conditions, which destroys the chemicals safely. The problem? Accessibility. In the UK, while take-back options exist, they’re not always easy to find. Many people live far from a drop-off point. Rural areas have fewer options. And if you don’t know they exist, you won’t use them. A 2023 report from the UK Environment Agency showed that only 1 in 4 people had ever used a take-back service. That’s not because people don’t care-it’s because they don’t know how or where.What You Can Do Today

You don’t need to wait for a government program to fix this. Here’s what works right now:- Check your medicine cabinet. Pull out anything expired, unused, or no longer needed. Don’t wait for a collection day.

- Call your pharmacy. Ask if they accept returns. Most do. If they say no, ask if they know where you can drop them off.

- Use a take-back event. The UK runs National Take Back Days twice a year, usually in April and October. Check your local council website or NHS site for dates.

- If no take-back is available, mix pills with something unappealing-used coffee grounds, kitty litter, or sawdust-seal them in a plastic container, and throw them in the trash. Never leave them in an open container.

- Never flush. Unless it’s on the FDA’s flush list (which is rare), don’t do it.

Why This Matters Beyond the Water

This isn’t just about fish or rivers. It’s about the long-term health of ecosystems and people. Pharmaceuticals in water contribute to antibiotic resistance-a crisis the WHO calls one of the top 10 global public health threats. When bacteria are constantly exposed to low levels of antibiotics, they evolve to survive. That means common infections could become untreatable. It’s also about fairness. People in low-income areas often live near landfills or polluted rivers. They’re exposed to these chemicals more than others, even though they’re less likely to be the ones flushing pills. Environmental justice isn’t just about pollution-it’s about who pays the price for it.What’s Changing?

There’s progress. In 2024, the UK government began piloting a new system where pharmacies must provide disposal instructions with every prescription. California passed a similar law in 2024. In the EU, manufacturers are now required to pay for take-back programs under Extended Producer Responsibility rules. That means drug companies are starting to fund the cleanup of their own waste. In Bristol, where I live, two pharmacies now offer year-round drop-off bins. A local campaign called ‘Return Your Pills’ has helped increase participation by 40% in two years. It’s not perfect, but it’s moving.Final Thought: Responsibility Isn’t Just Yours

You’re not the problem. The system is. Drug companies don’t design packaging for easy disposal. Doctors don’t always talk about what to do with leftovers. Governments don’t always make take-back easy to find. But you can still act. You can ask your pharmacist. You can tell your friends. You can refuse to flush. The next time you clean out your medicine cabinet, don’t reach for the toilet. Reach for the pharmacy. One pill at a time, we can stop poisoning our water.Is it ever okay to flush medications?

Only if the medication is on the FDA’s official ‘flush list’-a very short list of high-risk opioids like fentanyl and oxycodone that could cause fatal overdoses if misused. For all other medications, including painkillers, antibiotics, and heart meds, flushing is not recommended. Even if your doctor says it’s fine, check the label or ask your pharmacist. Most drugs should never go down the drain.

Can I just throw pills in the trash?

It’s better than flushing, but not ideal. Pills in landfills can leach into groundwater over time. To reduce risk, mix them with something unappetizing like coffee grounds, cat litter, or dirt. Put them in a sealed plastic container or ziplock bag before tossing them. This makes them less appealing to kids, pets, or people who might go through the trash. Never leave pills loose in a trash can.

Do take-back programs really make a difference?

Yes. Take-back programs are the only method that completely removes pharmaceuticals from the environment. Instead of entering water or landfills, collected medications are incinerated under strict controls that destroy the chemicals. Studies show that even small increases in participation reduce pharmaceutical levels in local waterways. In places where programs are well-publicized, like parts of Germany and California, environmental contamination has dropped significantly.

Why don’t more pharmacies offer take-back services?

Cost and logistics. Collecting and safely disposing of medications requires special handling, storage, and transport. Many pharmacies are small businesses without the budget or staff to manage it. Some local councils or health services fund these programs, but not everywhere. In the UK, participation is growing, but it’s still inconsistent. The government is working on making it mandatory, but it’s a slow process.

What about liquid medications or patches?

Same rules apply. Liquid medications should be mixed with an absorbent material like kitty litter or sawdust, sealed in a plastic container, and taken to a take-back location. Patches-especially opioid patches-should be folded in half with the sticky sides together before disposal. Some take-back sites accept them directly. Never flush liquids or throw patches in the trash without securing them. They’re just as dangerous as pills.

How do I find a take-back location near me?

Start by calling your local pharmacy. If they don’t take returns, ask them for the nearest drop-off point. You can also check your local council’s website or the NHS website for ‘medication disposal’ or ‘drug take-back’ services. In England, use the NHS Service Finder tool. In Wales, contact your local environmental health department. For national events, look up ‘National Take Back Day’-it happens twice a year and includes hundreds of locations across the UK.

Elizabeth Farrell

December 2, 2025 AT 09:43So many people just don’t realize how much damage this causes. I used to flush my old pills until I read about the fish with weird genitals in a science article. Now I keep a little ziplock bag in my bathroom cabinet just for expired meds. Took me six months to get my whole family on board, but now we all check our cabinets twice a year. It’s not perfect, but it’s something.

Also, if you live near a pharmacy that takes returns, go. Even if it’s just once a year. Small actions add up.

And no, mixing pills with coffee grounds doesn’t make it okay to toss them. It just makes the landfill smell weird.

Thanks for writing this. I shared it with my book club.

Sheryl Lynn

December 2, 2025 AT 10:19Oh darling, let’s not pretend this is some new revelation. The pharmaceutical-industrial complex has been offloading its toxic legacy onto the commons since the 70s. We’re not just talking about ibuprofen here-we’re talking about endocrine disruptors, neurotoxins, and antibiotic-resistant superbugs swimming in the Thames while some CEO sips sparkling water in a penthouse overlooking it. The real crime? The fact that we’re still debating ‘disposal methods’ instead of demanding corporate accountability. If Bayer or Pfizer had to pay for the cleanup, we wouldn’t need ‘take-back programs.’ We’d have zero pills in the water.

Also, ‘mix with kitty litter’? How quaint. That’s like putting a Band-Aid on a hemorrhage.

Genesis Rubi

December 2, 2025 AT 17:30flushing meds? thats what happens when you let libs run everything. in my day we just threw em in the trash like normal people. now we got these fancy programs and eco-guilt trips. who even cares if some fish get weird? its not like we drink that water. besides, america is the greatest country in the world and we dont need no fancy europe rules. if you cant afford to buy new pills then dont take em in the first place. problem solved. #makeamericaflushagain

Doug Hawk

December 2, 2025 AT 20:46Interesting data on the 80% river contamination rate but the methodology’s shaky-most studies use LC-MS/MS which has detection limits in the ng/L range. Are we sure these concentrations are biologically relevant? Also, the FDA flush list is often misinterpreted. It’s not a blanket permission-it’s a risk-benefit calculus for opioids specifically. The real bottleneck is infrastructure. Wastewater plants aren’t designed for micropollutants. Advanced oxidation? Activated carbon? Those are expensive. We need targeted funding, not just awareness campaigns.

And yes, mixing with cat litter is still landfill-bound. But it’s better than bioaccumulation in aquatic food chains. Trade-offs, people.

John Morrow

December 3, 2025 AT 19:48The entire premise is emotional manipulation wrapped in pseudoscientific alarmism. Nanograms per liter? That’s less than a grain of salt in an Olympic pool. We’re talking trace contaminants. The real threat is the overregulation and fearmongering that turns simple human behavior into a moral failing. People flush pills because they’re tired, overwhelmed, and don’t have time to chase down a pharmacy that might or might not be open. The solution isn’t guilt-it’s convenience. Make take-back bins as ubiquitous as cigarette receptacles. Until then, stop pretending this is an environmental apocalypse.

Also, ‘drug-resistant bacteria’? That’s from overprescribing, not from your grandma’s leftover antibiotics. Don’t conflate causation with correlation.

Kristen Yates

December 3, 2025 AT 23:49I learned about this from my sister who works at a clinic. She said they get boxes of expired meds every week from people who don’t know what to do. I started keeping a shoebox in my closet for old pills. I take it to the pharmacy when I go for my refill. It’s not much, but I feel better about it. I wish more people knew this was an option. Maybe if doctors mentioned it when they handed out prescriptions, it would stick.

Also, I never flush. Ever. Even if it’s just one pill.

Saurabh Tiwari

December 4, 2025 AT 10:30so true man 🤔 i never thought about this before but now i get it

in india we just throw everything in the dustbin but now i think maybe we should ask pharmacy

also my aunty still uses expired painkillers 😅

thanks for sharing this

✌️

Michael Campbell

December 4, 2025 AT 21:40They’re lying about the fish. It’s all part of the climate hoax. They want you to feel guilty so you’ll give up your meds. And the ‘take-back’ programs? That’s how they track who’s taking what. Next thing you know, they’ll be denying prescriptions based on your ‘environmental footprint.’

Don’t fall for it. Flush if you want to. They’re not coming for your pills. They’re coming for your freedom.

Victoria Graci

December 5, 2025 AT 15:36This isn’t just about water-it’s about the invisible threads connecting our personal choices to planetary health. We treat medicine like disposable consumer goods, but it’s not. It’s a synthetic compound with a lifecycle we refuse to acknowledge. The pill you flush carries the weight of industrial chemistry, corporate profit, medical overprescription, and cultural ignorance. It’s a tiny artifact of modernity’s broken feedback loops.

And yet-we still have agency. Not to fix the system overnight, but to refuse to be its passive vessel. Choosing the pharmacy over the toilet isn’t activism. It’s reclamation. It’s saying: I will not outsource my responsibility to a system that designed itself to be ignored.

Maybe that’s the real medicine we need.

Saravanan Sathyanandha

December 7, 2025 AT 12:27As someone from India, I can confirm that this issue is grossly under-discussed in developing nations. In many rural areas, expired medicines are simply buried or dumped in rivers due to lack of awareness and infrastructure. The Western-centric focus on take-back programs overlooks the fact that systemic solutions must be adapted to local realities. Perhaps instead of importing U.S.-style pharmacy drop-offs, we need community-based collection drives led by local health workers, combined with school education programs. The environmental burden is global, but the solutions must be contextual. Thank you for highlighting this-it’s a conversation we desperately need to have beyond the Global North.

alaa ismail

December 8, 2025 AT 20:49my mom always told me to flush pills. i thought it was the right thing. now i feel kinda bad. gonna check my cabinet this weekend.

also, why do they even make so many pills? why not just prescribe what you need?

ruiqing Jane

December 9, 2025 AT 22:57Thank you for writing this with such clarity. I’ve been quietly collecting expired medications in my closet for two years now-waiting for a take-back event that never came. I finally found one last month at the library. I brought 17 bottles. I cried. Not because I felt guilty-but because I realized how many people are just waiting for someone to show them the way. You did that. And I’m not alone anymore.

If you’re reading this and you’ve been holding onto pills out of fear or confusion-you’re not careless. You’re just unguided. Reach out. Call your pharmacist. Even if they say no, ask again. They’re not used to being asked. And if you’re a healthcare provider? Start talking about disposal during every prescription. It’s not extra work. It’s care.

Fern Marder

December 11, 2025 AT 12:36Wow. You really think people care about fish? 😒 Most of us are just trying to survive. You’re out here acting like you’re saving the planet while your Uber Eats order arrives in a plastic bag. 🙄

Just flush it. Nobody’s watching. And if they are? They’re probably just jealous you’re not on their ‘eco-woke’ checklist. 💅