Kidney Transplant Decision Calculator

Transplant vs. Dialysis Comparison

| Aspect | Kidney Transplant | Long-Term Dialysis |

|---|---|---|

| Life expectancy | ↑ 10-15 years vs. dialysis (average 5-7 years) | Limited; mortality rises after 5 years |

| Quality of life | Near-normal activity, less dietary restriction | Three-times-weekly sessions, strict fluid/food limits |

| Cost (NHS) | One-off £45k-£55k (cost recouped after ~2 years) | £30k-£40k per year |

| Complication risk | Rejection (10-15% first year), infection, medication side-effects | Vascular access infection, cardiovascular strain |

| Waiting time | Living donor: weeks-months; deceased donor: years | Immediate, but lifelong commitment |

Quick Take

- Kidney transplant replaces a failing organ and can restore normal life expectancy.

- Eligibility depends on overall health, donor availability, and thorough evaluation.

- Living donors offer better outcomes than deceased donors, but both are viable.

- Immunosuppressive drugs are essential; they prevent rejection but raise infection risk.

- Compared with long‑term dialysis, transplantation usually improves quality of life and reduces medical costs.

When a patient faces end‑stage renal disease, kidney transplant is the surgical replacement of a failing kidney with a healthy donor organ. The promise of a return to near‑normal kidney function makes it a tempting answer to the question, “Is this the ultimate solution to renal failure?” Below we break down what the procedure really involves, who can benefit, and where the trade‑offs lie.

What Is Renal Failure, and Why Does It Matter?

Renal failure also called end‑stage chronic kidney disease (CKD), occurs when the kidneys can no longer filter waste, balance electrolytes, or regulate fluid. In the UK, around 5% of adults have CKD, and roughly 10,000 progress to end‑stage each year, requiring either dialysis or a transplant.

The main symptoms-fatigue, swelling, shortness of breath, and anemia-stem from toxin buildup. Left untreated, renal failure can lead to cardiovascular disease, bone disorder, and eventual death. The two standard treatments are:

- Long‑term dialysis (hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis)

- Kidney transplantation

Understanding the limits of dialysis helps frame the value of a transplant.

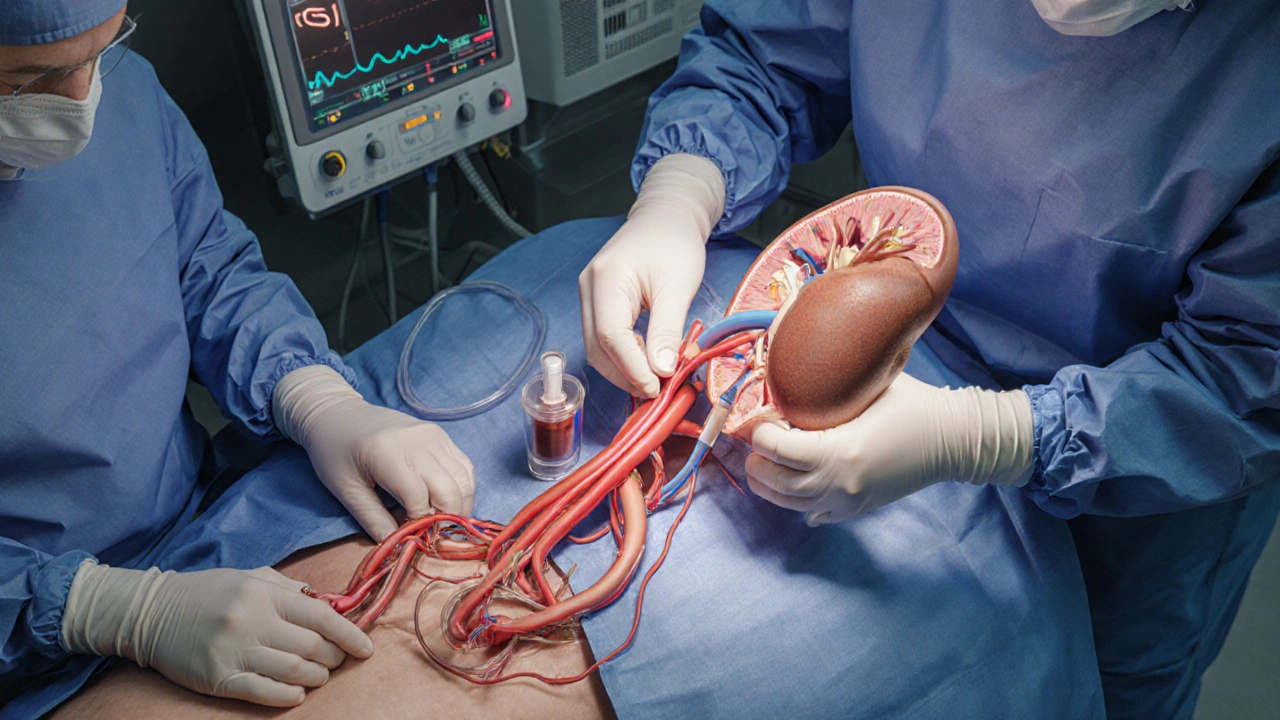

How a Kidney Transplant Works

During transplant surgery, a donor kidney is placed in the recipient’s lower abdomen and connected to the blood vessels and bladder. The operation typically lasts 3-4hours, and most patients leave the hospital after 5-7days.

Key steps include:

- Donor organ retrieval - either from a deceased donor after brain death or from a living donor undergoing a minimally invasive laparoscopic surgery.

- Recipient preparation - anesthesia, placement of monitoring lines, and removal of the diseased kidney (often left in place).

- Vascular anastomosis - suturing the donor’s renal artery to the recipient’s iliac artery and the renal vein to the iliac vein.

- Ureteral connection - linking the donor ureter to the bladder to allow urine drainage.

- Reperfusion - restoring blood flow; the new kidney typically begins producing urine within minutes.

Post‑operative care hinges on immunosuppressive therapy a regimen of drugs that keep the immune system from attacking the new organ. Common agents include tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and low‑dose steroids.

Who Can Receive a Transplant? - Evaluation and Donor Types

Eligibility is not a blanket “anyone with kidney failure.” A comprehensive evaluation looks at:

- Cardiovascular health - heart disease can raise surgical risk.

- Infection status - active infections must be cleared first.

- Cancer history - certain malignancies require a waiting period.

- Psychosocial support - patients need a reliable network for medication adherence.

Two donor categories dominate the UK waiting list:

- Living donor a friend, family member, or altruistic stranger who donates one of their two kidneys. Living donation shortens waiting time, offers better graft survival (85% at 5years), and reduces surgical complications.

- Deceased donor organs recovered after brain death or circulatory death. Availability depends on national organ‑sharing networks, and median wait time in England is about 3-4years.

Regardless of source, the donor‑recipient match is evaluated based on blood type, HLA antigens, and cross‑match testing to minimise rejection risk.

Kidney Transplant vs. Dialysis - A Side‑by‑Side Look

| Aspect | Kidney Transplant | Long‑Term Dialysis |

|---|---|---|

| Life expectancy | ↑ 10-15years vs. dialysis (average 5-7years) | Limited; mortality rises after 5years |

| Quality of life | Near‑normal activity, less dietary restriction | Three‑times‑weekly sessions, strict fluid/food limits |

| Cost (NHS) | One‑off £45k-£55k (cost recouped after ~2years) | £30k-£40k per year |

| Complication risk | Rejection (10‑15% first year), infection, medication side‑effects | Vascular access infection, cardiovascular strain |

| Waiting time | Living donor: weeks-months; deceased donor: years | Immediate, but lifelong commitment |

The numbers show why many clinicians view transplantation as the “gold standard” when a suitable donor exists. However, the decision hinges on personal health, donor availability, and willingness to accept lifelong medication.

Risks, Complications, and Long‑Term Care

Even with a successful operation, patients face several challenges:

- Acute rejection the immune system attacks the new kidney within weeks to months. Early detection via regular blood tests (creatinine, eGFR) and a prompt increase in immunosuppression usually saves the graft.

- Chronic rejection - a slower loss of function occurring after 5-10years, often linked to sub‑optimal medication levels.

- Infection - especially viral (CMV, BK virus) and fungal infections due to suppressed immunity.

- Medication side‑effects - nephrotoxicity from tacrolimus, metabolic syndrome from steroids, and heightened cancer risk.

- Cardiovascular disease - still the leading cause of death post‑transplant, so lifestyle changes are essential.

Long‑term follow‑up includes:

- Monthly blood work for the first six months, then quarterly.

- Annual kidney biopsies only if function declines.

- Vaccinations (influenza, pneumococcal, hepatitisB) as recommended.

Patients who stick to their medication schedule and attend appointments enjoy a median graft survival of 15years for living‑donor kidneys and 10years for deceased‑donor kidneys in the UK.

Cost, Access, and the UK Perspective

The NHS funds both dialysis and transplantation for residents. While the upfront cost of a transplant (£45‑£55k) seems steep, the cumulative expense of dialysis (£30‑£40k per year) quickly surpasses it. This economic reality drives policy to prioritize transplants, especially from living donors.

Key access points:

- Referral to a renal specialist as soon as eGFR drops below 30ml/min/1.73m².

- National organ allocation via the UK Transplant Registry - patients are scored on medical urgency, waiting time, and HLA match.

- Living‑donor programs at major centres such as Bristol Royal Infirmary, Guy’s Hospital, and Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust.

Financial assistance for donor travel, accommodation, and post‑donation recovery is provided through NHSLiving Donor Support schemes.

Putting It All Together - How to Decide

Choosing between dialysis and transplantation is a personal calculus. Here’s a quick decision framework:

- Health status - Are you free of uncontrolled heart disease, active infection, or recent cancers?

- Donor availability - Do you have a willing, compatible living donor, or are you prepared for a potentially long waiting list?

- Lifestyle goals - Do you want the flexibility to travel, work full‑time, and avoid thrice‑weekly clinic trips?

- Risk tolerance - Are you comfortable with lifelong immunosuppression and its monitoring?

- Support network - Can family or friends help you with medication management and appointments?

If the answers line up, transplantation is likely the “ultimate solution” for many. If any major barrier exists, dialysis remains a life‑sustaining bridge while you explore other options, such as paired‑exchange programs or emerging technologies like bioengineered kidneys (still experimental in 2025).

Frequently Asked Questions

How long does a kidney transplant last?

For living‑donor kidneys, 80‑85% still function after five years, and about 50‑55% last ten years. Deceased‑donor kidneys have slightly lower survival, with roughly 70% active at five years. Advances in immunosuppression are slowly pushing these numbers upward.

Can I receive a transplant if I’m on dialysis?

Absolutely. Most transplant candidates are already on dialysis while they wait. In fact, dialysis can keep you stable enough to undergo the extensive pre‑transplant work‑up.

What are the biggest risks after surgery?

Early - acute rejection, infection, and surgical complications (bleeding, urine leak). Long‑term - chronic rejection, medication‑related side‑effects, and cardiovascular disease.

Do I need a donor match for blood type?

Yes. Blood type compatibility is the first filter (e.g., O donor can give to any blood type, but an O recipient can only receive from O). After that, HLA matching further reduces rejection risk.

How is the donor kidney screened?

The organ undergoes serological testing for infections (HIV, hepatitis), imaging to assess structure, and a biopsy if needed. Donor age, kidney function, and warm‑ischemia time are also recorded.

angelica maria villadiego españa

October 3, 2025 AT 09:43Reading through the transplant vs. dialysis comparison really hits home for anyone facing kidney failure. It’s clear that a transplant can give back years of life and a lot more freedom, especially when you have a living donor lined up. The quality‑of‑life boost-being able to travel, work, and eat without the strict fluid limits of dialysis-is something many patients long for. At the same time, the prep work, like heart‑health checks and infection screenings, isn’t something to skim over. If you’re in good overall health and have a supportive network, the numbers in the table make a strong case for going for a transplant. Don’t forget the lifelong meds, though; they do require diligent monitoring. All in all, if the medical team thinks you’re a good candidate, the transplant route often feels like the best path forward.

Ted Whiteman

October 12, 2025 AT 12:23Ah, the glamorous promise of a new kidney, right? Let’s not pretend it’s all rainbows and sunshine. You trade one set of risks for another-immunosuppressants that turn your body into a playground for infections, and the ever‑looming threat of rejection that can strike at any moment. The waiting game for a deceased donor can stretch into years, and even a living donor isn’t a guarantee of a smooth ride. Remember, dialysis, despite its grind, is a proven steel‑rod that keeps you alive while you wait for that perfect match. So before you jump on the transplant hype train, keep your eyes wide open about the long‑term battle you’re signing up for.

Dustin Richards

October 21, 2025 AT 15:03Dear reader, the evaluation process for kidney transplantation is rigorously structured to ensure optimal outcomes. Candidates undergo comprehensive cardiac assessment, infection screening, and psychosocial evaluation, all of which are indispensable for postoperative success. The presence of a compatible living donor markedly shortens the waiting period and improves graft survival rates, as reflected in recent UK data. While the surgical procedure itself is generally well‑tolerated, the lifelong commitment to immunosuppressive therapy demands strict adherence and regular monitoring. In summary, when the medical criteria align, transplantation remains the gold standard for restoring renal function.

Vivian Yeong

October 30, 2025 AT 16:43The data simply shows that transplantation isn’t a miracle cure for everyone.

suresh mishra

November 8, 2025 AT 19:23For a quick fact: living‑donor kidneys have about an 85% five‑year graft survival rate, compared to roughly 70% for deceased donors.

Reynolds Boone

November 17, 2025 AT 22:03One thing people often overlook is the impact of post‑transplant lifestyle counseling. Exercise, diet, and mental health support dramatically lower cardiovascular risks that remain the top cause of mortality after a successful graft. Clinics that integrate a multidisciplinary team-nutritionists, physiotherapists, and counselors-see better long‑term outcomes. So if you’re considering a transplant, ask your center about those extra resources; they can make a huge difference.

Angelina Wong

November 27, 2025 AT 00:43Don’t let the fear of medication side‑effects hold you back from a chance at a normal life. With proper dosing and regular blood work, most patients manage immunosuppressants without major issues. Think of the freedom to travel, the ability to hold a full‑time job, and the return to hobbies you thought were lost. Stay motivated, stay compliant, and you’ll reap the benefits of a thriving new kidney.

Anthony Burchell

December 6, 2025 AT 03:23Everyone’s quick to hail transplantation as the ultimate fix, but let’s flip the script. The reality is that you’re swapping one chronic condition for another, with a cocktail of drugs that can wreck your metabolism, cause mood swings, and leave you vulnerable to nasty infections. Even the best‑matched kidneys can fail after a decade, sending you back to the dialysis treadmill you thought you escaped. So before you jump on the hype, weigh the perpetual trade‑offs; sometimes staying on dialysis with a solid support system is the smarter, safer bet.

Michelle Thibodeau

December 15, 2025 AT 06:03When you stare at the numbers in the transplant vs. dialysis table, it feels like a crossroads of destiny and science. On one side, you have the promise of an extra decade or two, the gleam of waking up without the dreaded dialysis machine humming in the background. On the other, there’s the undeniable reality that a transplanted kidney is not a magical, forever‑young organ; it ages, it can be rejected, and it demands a lifelong partnership with potent drugs. Yet, the human spirit is remarkably resilient, and when a patient embraces that partnership with diligence, the rewards can be profound. Imagine the simple joy of drinking a glass of water without counting each sip, or the liberty to board a last‑minute flight for a loved one’s wedding. Those moments, often taken for granted, become priceless milestones after a successful graft. Of course, the road to those milestones is paved with rigorous testing-cardiac assessments, infection screens, psychosocial evaluations-all designed to ensure the body is ready for such a monumental change. If a living donor steps forward, the waiting time shrinks dramatically, and the graft’s longevity improves, a fact reflected in the striking 85% five‑year survival rate for living‑donor kidneys. Conversely, the waiting list for deceased donors can stretch years, a period during which patients must rely on dialysis’s unrelenting schedule. That schedule, while life‑sustaining, can erode quality of life, imposing dietary restrictions and limiting flexibility. It’s a paradox: you’re alive, yet life feels constrained. The economic perspective adds another layer; the upfront cost of a transplant may seem steep, but the cumulative expense of dialysis over a decade dwarfs it, influencing policy decisions that favor transplantation. Moreover, the post‑transplant journey isn’t over after the surgery; it demands unwavering commitment to medication adherence, regular lab work, and lifestyle modifications to stave off cardiovascular disease, the leading cause of death even after a successful transplant. Yet, for many, that commitment feels like an investment in reclaimed freedom. In the grand tapestry of renal failure management, transplantation isn’t a one‑size‑fits‑all miracle, but for those who meet the medical criteria, have a supportive network, and are ready to embrace the lifelong stewardship of their new organ, it often stands as the most hopeful pathway to a fuller, richer life.

Patrick Fithen

December 24, 2025 AT 08:43Consider the kidney as a silent philosopher, quietly filtering the body’s truths while the world rushes on. When we replace it, we’re not just swapping tissue; we’re negotiating with destiny, asking whether we can rewrite the narrative of our own mortality. The decision to transplant becomes a dialogue between the self and the larger tapestry of medical possibility, echoing ancient debates about body and soul. In the end, the choice reflects not only clinical data but the personal saga each patient carries, a story measured in hopes, fears, and the quiet resilience of the human heart.