When you're pregnant or breastfeeding, even a simple headache pill can feel like a high-stakes decision. That’s why drug labels now include detailed information about pregnancy and breastfeeding risks - but they don’t look the way they used to. If you’re confused by the new format, you’re not alone. The old letter system (A, B, C, D, X) is gone. In its place is a more detailed, narrative-based approach called the Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule (PLLR), which took full effect in 2020. This isn’t just paperwork - it’s meant to help you and your doctor make smarter, safer choices. Here’s how to actually read and use it.

What Replaced the Old Pregnancy Letters?

For decades, drugs were labeled with letters: A, B, C, D, or X. A meant “safe,” X meant “dangerous,” and everything else was a gray zone. But here’s the problem: those letters didn’t tell you anything real. A Category B drug? That didn’t mean it was safe. It just meant animal studies showed no harm - but human data was missing. And Category C? That applied to 70% of all prescription drugs. It was meaningless noise. The FDA got rid of the letters in 2015 because doctors and patients kept misusing them. A 2017 FDA study found 68% of people thought the letters were a safety grade - like a school report card. They weren’t. So the FDA replaced them with three clear sections inside every drug label: Pregnancy (8.1), Lactation (8.2), and Females and Males of Reproductive Potential (8.3). Each one follows the same structure: Risk Summary, Clinical Considerations, and Data. No more guessing. Just facts.How to Read the Pregnancy Section (8.1)

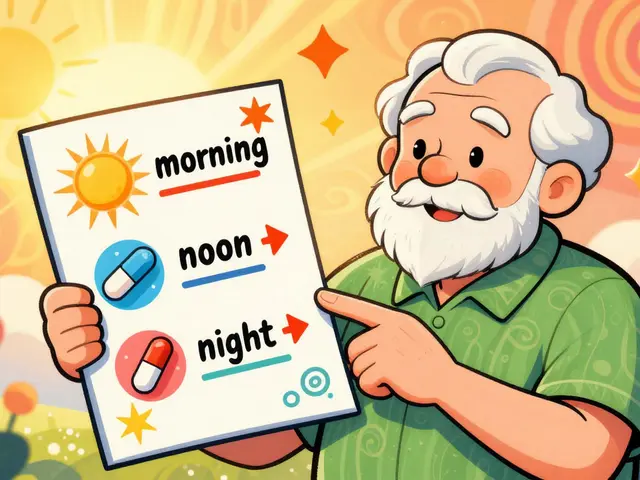

The Pregnancy section starts with the Risk Summary. This isn’t a vague warning. It tells you the actual chance of birth defects or miscarriage - and how the drug changes that risk. For example, you might see: “The background risk of major birth defects in the U.S. general population is 2-4%. Exposure to this drug during the first trimester is associated with a 1.5-fold increased risk of neural tube defects.” That means if the normal risk is 3%, and the drug doubles it, the new risk is about 4.5%. Not scary. Not safe. Just clear. Then comes Clinical Considerations. This is the part that tells you what to do. It might say: “Avoid use in the first trimester if possible. If used after 20 weeks, monitor fetal growth every 4 weeks.” Or: “This drug has been safely used in over 1,200 pregnancies with no increased risk of preterm birth.” These are actionable, not theoretical. Finally, the Data section. This is where the science lives. It tells you how they got the numbers: Was it a study of 100 women? 1,000? Were the women taking other drugs too? Was it a randomized trial or just observations? If you’re curious - or skeptical - this is where you find out.Understanding Lactation Labeling (8.2)

Breastfeeding moms face a different question: “Will this drug get into my milk? And will it hurt my baby?” The Lactation section answers both. It starts with Risk Summary, which gives you numbers: “Maternal dose of 50 mg daily results in an infant exposure of 2.3% of the maternal weight-adjusted dose.” That’s tiny - less than 1/40th of what mom takes. Most drugs fall below 10%. The section will also say if there are any reported side effects in breastfed infants: drowsiness, fussiness, low milk supply. Clinical Considerations tells you how to use it safely: “Feed infant immediately before taking dose to minimize exposure.” Or: “Avoid breastfeeding for 4 hours after dose if infant is premature.” These aren’t guesses. They’re based on how the drug moves through your body. And again - Data shows you the science. Was the milk tested in 15 mothers? Were the babies monitored for 6 weeks? Was the drug measured in blood or just urine? The more detail, the more trustworthy it is.

What About Fertility and Contraception? (8.3)

This section isn’t just for women. It’s for anyone who can get pregnant - or whose partner can. It answers: “Do I need to avoid pregnancy while taking this? How long after stopping can I try?” You’ll see things like: “Females of reproductive potential should use effective contraception during treatment and for 3 months after the last dose. Contraceptive failure rate with oral pills is 7% per year.” Or: “This drug may cause reversible infertility in males. Sperm count returns to normal within 6 months after discontinuation.” It’s not about scare tactics. It’s about planning. If you’re trying to conceive, you need to know if you should stop the drug, switch it, or wait.Why This System Is Better - and Harder

The new system is smarter. It doesn’t hide behind letters. It tells you the real numbers. It gives you timing: “Risk is highest in weeks 6-10.” It tells you about registries tracking outcomes - like the one for antidepressants that now includes data from over 25,000 pregnancies. But it’s not easy. A 2018 study found 62% of OB-GYNs felt overwhelmed at first. Family doctors, who often handle routine prescriptions, were even more unsure. Why? Because you can’t glance at a label and say “C = avoid.” You have to read. You have to think. That’s why many doctors now use tools like MotherToBaby or TERIS - free services that summarize PLLR data in plain language. Pharmacists are spending 5-7 extra minutes per prescription counseling patients. Patients are asking more questions. That’s a good thing. It means people are actually understanding the risks.What to Do When You’re Confused

You don’t have to be a doctor to use this. Here’s what works:- Look for the Risk Summary first. What’s the baseline risk? What’s the drug’s added risk? If it says “no increased risk,” that’s the best-case scenario.

- Check the Clinical Considerations. Are there clear instructions? Do they say “avoid,” “monitor,” or “safe”? That’s your action plan.

- Don’t panic over “increased risk.” A 2-fold increase from 1% to 2% is still low. Ask your provider: “What’s the absolute risk?”

- Use free resources. MotherToBaby (1-800-733-4727) and the FDA’s PLLR Navigator app give you summaries in plain English.

- Ask your pharmacist. They’re trained to interpret these labels now. They see them every day.

What’s Next for Drug Labeling?

The FDA is working on making this even clearer. In 2023, they started testing visual icons - like a tiny baby with a red slash for high risk, or a green check for low risk - to go alongside the text. By 2025, they plan to update every pregnancy-related label. They’re also pushing for better data. Right now, only 15% of pregnancy registry participants are Black or Hispanic - even though those groups make up 30% of U.S. pregnancies. That’s a gap. And it’s being fixed. The goal isn’t perfection. It’s honesty. No more misleading letters. No more silence. Just facts - so you can decide what’s right for you and your baby.Common Questions About Drug Labels During Pregnancy and Breastfeeding

Are all drugs now labeled with the new PLLR format?

As of 2026, about 78% of prescription drugs in the U.S. have updated PLLR labeling. All new drugs approved since 2015 use the new format. Older drugs were required to switch by 2020, but some generics and older medications may still have the old letter system. Always check the most recent package insert - it should say “Revised: [date]” under the section headings.

What if the label says there’s “insufficient data”?

That means no good human studies exist - not that the drug is dangerous. Many medications, especially newer ones, fall into this category. In these cases, doctors rely on animal data, similar drugs, or registries. Talk to your provider about alternatives. Sometimes, the safest choice is to avoid the drug entirely - or use a better-studied one.

Can I trust the numbers on the label?

Yes - but understand the source. The data comes from pregnancy exposure registries, published studies, and clinical trials. The FDA requires manufacturers to submit real-world data. However, most studies are observational, not randomized. That means they show association, not always cause. Always ask: “How many women were studied? Were there other factors?”

Is it safe to take antidepressants while breastfeeding?

Many antidepressants are considered low risk. For example, sertraline and paroxetine show infant exposure under 5% of the maternal dose. The Clinical Considerations section often recommends them as first-line options for breastfeeding mothers. Untreated depression can be more harmful than the medication. Always discuss options - don’t stop cold turkey.

What if I took a drug before I knew I was pregnant?

Most drugs don’t cause harm during the first few weeks of pregnancy - before the embryo implants. This is called the “all-or-nothing” period. If something went wrong, the pregnancy usually wouldn’t continue. If you’re worried, contact MotherToBaby or your OB-GYN. They can look up your specific drug and timing. In most cases, the risk is low - and knowing helps reduce anxiety.

Do over-the-counter (OTC) drugs have PLLR labels?

No. The PLLR only applies to prescription drugs. OTC medications like ibuprofen or acetaminophen have warning labels on the box, but they’re not as detailed. For OTCs, consult your pharmacist or use MotherToBaby’s OTC database. Even “natural” supplements aren’t regulated the same way - and can carry hidden risks.

Next Steps for Patients and Providers

If you’re pregnant or breastfeeding and taking medication:- Ask for the latest FDA-approved package insert - not just the pharmacy label.

- Use the PLLR Navigator app or MotherToBaby to get plain-language summaries.

- Don’t stop or change your medication without talking to your doctor. Sudden changes can be riskier than the drug itself.

- Keep a list of all drugs you’re taking - including supplements - and review it at every visit.

- Use clinical decision support tools built into your EHR - but verify they’re using the latest PLLR data.

- Attend free FDA training modules on PLLR interpretation.

- Keep a printed quick-reference guide for common drugs (e.g., antihypertensives, antiepileptics, SSRIs).

Ashlee Montgomery

January 11, 2026 AT 14:48The new PLLR system finally treats patients like adults who can handle real data instead of babyish letters. No more guessing games. Just facts about risk, timing, and exposure. It’s about time the FDA stopped coddling us.

Ted Conerly

January 12, 2026 AT 21:26I’ve been using this system since 2021 as a pharmacist and let me tell you - patients are asking better questions now. They’re not just panicking over ‘Category C’ anymore. They’re reading the clinical considerations and showing up with specific concerns. That’s progress.

Ian Cheung

January 13, 2026 AT 09:27Most people don’t realize how much work goes into these labels. I used to think they were just legal disclaimers but now I check the data section - sample sizes, study designs, whether they controlled for other meds. Turns out half the old ‘safe’ drugs had zero human data. Scary stuff.

Mario Bros

January 14, 2026 AT 03:45My wife was on sertraline during both pregnancies. The label said infant exposure under 5%. We called MotherToBaby. They walked us through it. No panic. Just facts. Best decision we ever made.

Christine Milne

January 16, 2026 AT 01:13While the FDA’s new labeling system may appear to offer greater transparency, one must not overlook the systemic bias inherent in the data collection protocols. The overwhelming majority of studies derive from predominantly white, middle-class cohorts - a demographic that constitutes less than 40% of the U.S. maternal population. To suggest this represents ‘honesty’ is, frankly, a form of institutional epistemic violence.

Lisa Cozad

January 17, 2026 AT 13:25I read the label for my prenatal vitamin and it said ‘no increased risk’ - but then I looked up the data section and saw it was based on 87 women. Not exactly a massive sample. Still, better than nothing. I’m keeping it.

Saumya Roy Chaudhuri

January 18, 2026 AT 22:22They say the letters were misleading but now we get paragraphs of jargon that make my head spin. Who has time to read 12 pages of clinical considerations just to take a Tylenol? This isn’t progress - it’s bureaucratic overreach disguised as empowerment.

Faith Edwards

January 19, 2026 AT 20:25It is profoundly disheartening that the general populace still clings to the notion that medical information should be ‘easy’ - as if pregnancy were a Netflix show one can binge without intellectual engagement. The very premise of informed consent demands cognitive labor. To demand simplification is to surrender autonomy.

Jake Nunez

January 20, 2026 AT 11:30As someone who moved here from India, I was shocked how detailed this is compared to what we had back home. In Delhi, doctors just said ‘avoid’ or ‘fine’ - no numbers, no timing, no data. This system? It’s a gift. Even if it takes time to learn.

neeraj maor

January 22, 2026 AT 01:10Let’s be real - the FDA didn’t change this for safety. They changed it because Big Pharma wanted to avoid liability. Now every drug has a 2000-word disclaimer so no one can sue. And those ‘free’ resources? They’re funded by the same companies that make the drugs. The transparency is a smokescreen.

Ritwik Bose

January 22, 2026 AT 20:34Thank you for this clear breakdown 🙏. I’ve shared this with my sister who’s pregnant and was terrified of every medication. Now she’s reading the labels herself and feels empowered. That’s what real healthcare looks like.

Jay Amparo

January 24, 2026 AT 00:46My wife took lamotrigine during her pregnancy. The label said ‘no increased risk of major malformations in over 1,200 cases.’ We cried when we read that. Not because we were relieved - but because for the first time, someone had actually told us the truth without sugarcoating it. This isn’t just labeling. It’s dignity.

Michael Marchio

January 25, 2026 AT 03:03People think this system is better because it’s ‘transparent’ - but let’s not pretend it’s not just another way to overwhelm the average person into submission. You want honesty? Fine. But then stop pretending that a layperson can meaningfully interpret statistical risk ratios without a biostatistics degree. This isn’t empowerment - it’s a guilt trip disguised as education. And don’t get me started on the fact that the FDA still hasn’t fixed the racial data gap. They’re not fixing the system. They’re just making it more complicated while patting themselves on the back.