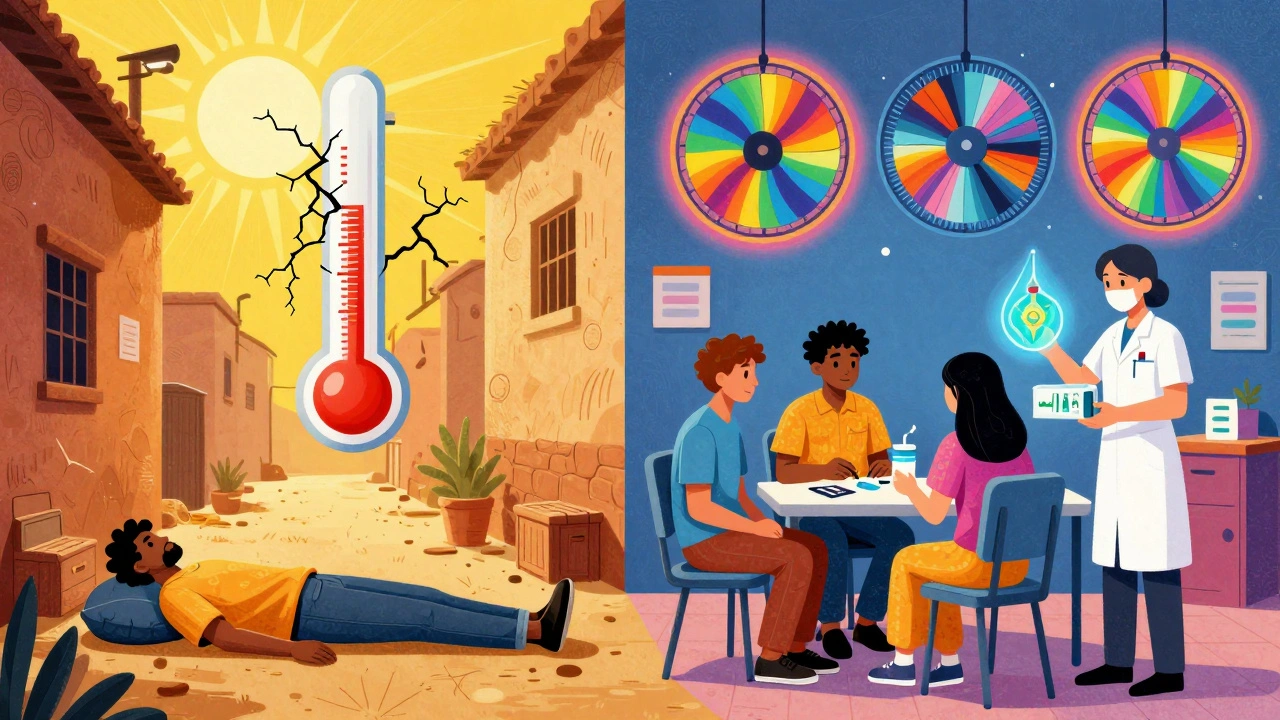

When the temperature climbs above 24°C (75.2°F), something dangerous happens to people who use drugs: their risk of overdose spikes. It’s not just about being hot. It’s about your body breaking down under pressure-heat, dehydration, and drugs all teaming up to push you past the edge. This isn’t theoretical. In New York City, emergency calls for overdoses jumped 22% during heat advisories between 2018 and 2022. In places like the Pacific Northwest, where summers used to be mild, overdose risk during heat domes rose more than three times higher than normal. And it’s getting worse. By 2050, climate models predict 20 to 30 extra days each year where temperatures cross that dangerous threshold.

Why Heat Makes Overdose More Likely

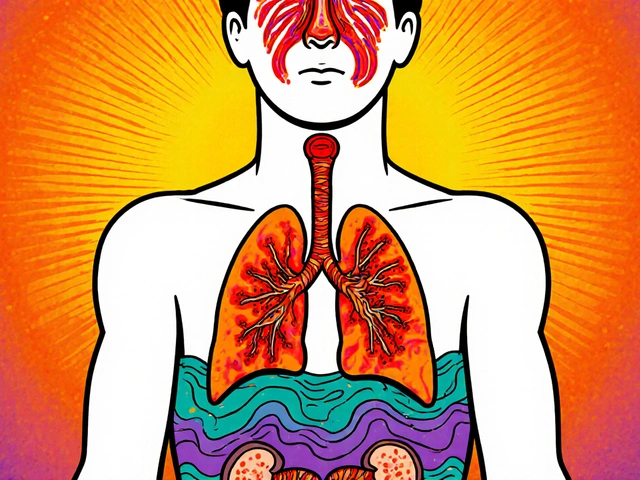

Your body works hard to stay cool. When it’s hot, your heart pumps faster-up to 25 extra beats per minute just to move blood to your skin. Now add cocaine, meth, or even high-dose opioids, and that strain multiplies. Stimulants already crank up your heart rate by 30-50%. Together, heat and drugs can overload your cardiovascular system. You don’t need to use a lot to die. Just a little extra heat can turn a normal dose into a lethal one.Dehydration makes it worse. Lose just 2% of your body weight in fluids-something easy to do in the heat-and your blood gets thicker. Drugs become more concentrated. That half-gram you usually take? In the heat, it might as well be three-quarters. Your liver and kidneys can’t process it as fast. Your body can’t sweat enough to cool down. And if you’re on medications for depression, anxiety, or psychosis, many of those drugs lose effectiveness or become more toxic in heat. About 70% of antipsychotics and 45% of antidepressants react badly to high temperatures, according to research in JAMA Internal Medicine.

For people using opioids, heat reduces your body’s ability to compensate for breathing slowdown. Normally, your body tries to breathe deeper when oxygen drops. Heat cuts that response by 12-18%. That means your brain doesn’t get the signal to wake up when your breathing slows too much. You don’t even feel like you’re in danger. That’s why so many overdoses happen quietly-alone, in a room with the blinds closed, no one around to notice.

Who’s Most at Risk

This isn’t a problem for everyone. It hits hardest where systems have already failed. People experiencing homelessness make up just 0.17% of the U.S. population, but they account for 38% of those with substance use disorders. Many sleep on concrete, in alleys, or under bridges-places that trap heat. Urban heat islands can be 5°C hotter than nearby parks or suburbs. For someone without air conditioning, that’s the difference between survivable and deadly.People in recovery are also vulnerable. Stopping drugs doesn’t mean your body forgets how to handle heat. Withdrawal can leave you dehydrated, shaky, and sensitive to temperature changes. Medications like buprenorphine, used for opioid treatment, lose up to 23% of their effectiveness above 30°C. If your dose isn’t adjusted, you might relapse just to feel normal. And if you’re not getting medical support during heatwaves, you’re on your own.

And then there’s the stigma. Shelters often turn people away if they’re actively using drugs. Outreach workers have had cooling supplies-electrolyte packets, misting towels-confiscated by police. People who need help the most are being pushed further out.

What You Can Do: Practical Harm Reduction Steps

You don’t need to quit to stay alive. You just need to adjust. Here’s what works, based on real programs that saved lives:- Reduce your dose by 25-30% when it’s over 24°C. Your body isn’t the same in the heat. What felt safe last week might kill you now.

- Drink one cup of cool water every 20 minutes. Not soda. Not energy drinks. Just plain water at 50-60°F. This keeps your blood from thickening and helps your body cool down. NYC’s harm reduction teams saw a 17% drop in heat-related overdoses after pushing this rule hard.

- Don’t use alone. If you’re going to use, make sure someone’s nearby who knows how to use naloxone. Text a friend. Call a peer support line. Don’t isolate.

- Use in a cool place. If you can’t get to air conditioning, go to a library, community center, or 24-hour convenience store. Even a shaded bus stop is better than a sun-baked sidewalk.

- Check your meds. If you’re on antidepressants, antipsychotics, or heart meds, talk to your provider before summer hits. Some need dose adjustments in heat. Others need to be switched.

And if you’re helping someone else: don’t wait for them to ask. Bring water. Ask if they’ve eaten. Check if they’re shivering or sweating too much. Heat exhaustion looks like confusion, dizziness, nausea. If they’re acting off, treat it like a medical emergency-even if you think it’s just "being high."

What Communities Are Doing Right

Some places are catching on. Vancouver set up seven air-conditioned respite centers next to supervised consumption sites during the 2021 heat dome. They didn’t turn people away. They gave them water, fans, and medical support. Overdose deaths dropped by 34% that summer.Philadelphia hands out over 2,500 cooling kits each year-free electrolyte packs, damp cooling towels, and cards with local shelter numbers. They don’t assume people know where to go. They bring the help to the streets.

In Maricopa County, Arizona, volunteers trained in naloxone and heat safety made over 12,000 wellness checks during the 2022 heat season. They didn’t judge. They just asked: "Are you okay? Do you need water?" And they saved 287 lives.

But here’s the problem: only 12 out of 50 U.S. states have official heat emergency plans that even mention drug use. Most cities still treat heat as a weather issue-not a public health crisis with a drug overdose component.

What Needs to Change

This isn’t just about individual choices. It’s about systems. Shelters need to be drug-inclusive. Emergency responders need training on heat-drug interactions. Clinics need to screen for heat vulnerability during every visit. The CDC’s Heat & Health Tracker shows that even in places like Seattle and Portland-where people aren’t used to heat-the overdose risk spikes faster than in Arizona or Texas. Why? Because people aren’t acclimated. Their bodies aren’t used to the stress.There’s a new federal push. The Biden administration’s 2023 executive order allocated $50 million to get overdose risk protocols into every state’s heat action plan by December 2025. That’s a start. But funding doesn’t mean change. Real change means:

- Training all EMS and police on how heat affects drug users

- Requiring shelters to allow people who use drugs during heat emergencies

- Providing free cooling supplies at pharmacies, libraries, and clinics

- Expanding access to air-conditioned harm reduction centers

And it means listening to people who use drugs. They’re not just statistics. They’re neighbors. Parents. Friends. People who survived trauma, poverty, and loss. They’re not asking for perfection. They’re asking to be seen.

What to Do Right Now

If you use drugs:- Keep a water bottle with you at all times. Refill it every hour.

- Know your local harm reduction center. Save their number in your phone.

- Carry naloxone. Even if you don’t use opioids, someone you know might.

- Use only when you’re not alone. Call someone before you do.

- Lower your dose. Always.

If you know someone who uses drugs:

- Check on them during heatwaves. A simple text: "Hey, you good?" can save a life.

- Don’t assume they’re fine because they’re not "acting high." Heat makes people quiet, confused, sleepy.

- Help them find shade or AC. Don’t wait for them to ask.

- Advocate. Tell your city council, your local health department: heat and drugs are a deadly mix. Make plans.

If you’re a service provider:

- Screen for heat risk using tools like CHILL’D-Out. Ask about housing, meds, hydration.

- Keep water, electrolytes, and cooling towels on hand.

- Partner with outreach teams. Don’t work in silos.

- Train your staff: heat exhaustion looks like overdose. Overdose looks like heat exhaustion.

This isn’t about morality. It’s about biology. Heat doesn’t care if you’re a "user," a "addict," or a "recovered person." It only cares if your body can handle the stress. And right now, too many systems are failing the people who need help the most.

Can heat really cause an overdose even if I don’t use drugs?

Yes-but not in the same way. Heat alone can cause heat stroke, which is life-threatening. But when someone uses drugs, the risk multiplies. Drugs interfere with your body’s ability to regulate temperature and breathing. So while a healthy person might get sick in extreme heat, someone using drugs is far more likely to die. The combination turns a medical emergency into a fatal one.

I’m on medication. Should I change my dose during a heatwave?

Talk to your doctor before the heat hits. Many psychiatric and heart medications become less effective or more toxic in high heat. Antipsychotics, antidepressants, and some blood pressure drugs can cause dangerous side effects when combined with heat. Don’t adjust your dose on your own. But don’t ignore the risk either. Ask your provider: "Should I change anything during summer?"

Why do some people die from overdose in air-conditioned homes?

Because the damage started before they got inside. If someone used drugs in the heat, their body was already under stress. Dehydration, elevated heart rate, and concentrated drug levels don’t disappear just because they walked into a cool room. The overdose can still happen hours later. That’s why it’s critical to monitor people for 6-12 hours after they’ve been in extreme heat, even if they seem fine now.

Is naloxone useful during heat-related overdoses?

Only if opioids are involved. Naloxone reverses opioid overdoses by blocking opioid receptors. But if someone overdosed because of cocaine, meth, or alcohol, naloxone won’t help. That’s why it’s important to know what was used. Still, keep naloxone on hand anyway. Many people use multiple drugs at once, and opioids are often mixed in unknowingly.

Can drinking too much water cause problems?

Yes-but not in the way most people think. Drinking plain water without electrolytes during heavy sweating can dilute sodium in your blood, leading to hyponatremia. That’s rare, though, and only happens with extreme overhydration (like 10+ liters in a few hours). For most people, drinking one cup every 20 minutes is safe and life-saving. If you’re sweating a lot, add a pinch of salt to your water or use electrolyte packets. They’re cheap, easy to carry, and widely available.

Where can I find cooling centers during a heatwave?

Call your local health department or 211 (in the U.S.) for a list of open cooling centers. Libraries, community centers, and public transit hubs often open their doors during heat emergencies. Some harm reduction organizations also run pop-up cooling stations. If you’re unsure, ask at a pharmacy or clinic-they usually know.

What if I’m turned away from a shelter during a heatwave?

That’s illegal in some places, but still common. Call your local harm reduction group or advocacy organization. They can help you find alternatives or pressure the shelter to change its policy. In the meantime, look for 24-hour convenience stores, bus stations, or public libraries. Even sitting in a shaded park with water is better than being alone in the sun.

Are there any apps or tools that help track heat risk?

The CDC’s Heat & Health Tracker shows real-time risk levels by county. Some cities have their own alerts. You can also sign up for local weather alerts that include heat advisories. But the best tool is a person. Keep a list of trusted contacts-someone who checks on you, someone you can call if you feel off. Technology helps, but human connection saves lives.

patrick sui

December 2, 2025 AT 04:13Yo, this is wild but makes total sense. The cardiovascular strain from heat + stimulants is basically a perfect storm-heart rate doubling, blood thickening, liver overloaded. I’ve seen it firsthand in Dublin during the 2022 heatwave. Harm reduction teams there started handing out electrolyte sachets at needle exchanges and saw a 20% drop in ER visits. We need this baked into public health policy, not just left to NGOs.

Also, the bit about antipsychotics losing efficacy above 30°C? JAMA Internal Medicine nailed it. Clinicians need to be trained on thermoregulatory pharmacokinetics, not just told to "watch for side effects."

Conor Forde

December 4, 2025 AT 03:46Ok but let’s be real-this isn’t about "overdose risk," it’s about the state abandoning its most vulnerable citizens. You think someone sleeping on concrete in Philly gives a damn about "reducing their dose by 25%" when they’re being chased off park benches by cops? This article reads like a rich person’s guilt pamphlet.

Meanwhile, the same cities that ignore this are spending millions on "smart city" sensors to track pigeons. Priorities, people.

Declan O Reilly

December 4, 2025 AT 20:09There’s something deeply human here. We talk about biology, pharmacokinetics, heat indices-but we forget that the person under the bridge isn’t a data point. They’re someone who survived abuse, war, neglect. They’re not choosing to use drugs because they’re lazy. They’re using because it’s the only thing that makes the silence stop.

And heat? It doesn’t discriminate. It doesn’t care if you’re a "recovering addict" or a "junkie." It just wants you to fail. The real tragedy isn’t the overdose-it’s that we built systems that make survival feel like a miracle.

So yeah, hydrate. Don’t use alone. But also-stop treating people like problems to manage. Treat them like people who deserve to live.

💙

Adrian Barnes

December 4, 2025 AT 20:46While the data presented is superficially compelling, the underlying premise is dangerously reductionist. To attribute overdose mortality primarily to environmental factors is to absolve individual agency and reinforce pathological dependency. The real issue is the normalization of substance abuse within a culture that no longer values self-discipline or personal responsibility.

Furthermore, the suggestion that shelters should accommodate active drug users is a moral hazard that incentivizes chronic dysfunction. The appropriate response is not air-conditioned respite centers, but mandatory rehabilitation protocols enforced by state authority.

Thermoregulatory physiology is irrelevant when the root cause is moral decay.

Declan Flynn Fitness

December 5, 2025 AT 06:50Just read this at the library during a heat alert. Had a guy come up to me sweating, shaking, said he took a hit earlier and felt "weird." Gave him a water bottle and a cooling towel I keep in my bag. He cried. Said no one’s ever asked if he was okay before.

Simple stuff. Doesn’t cost much. Doesn’t need a policy. Just needs people who care.

Also-naloxone in every damn backpack. Seriously. I carry two. I’m not a hero. I’m just not gonna let someone die because I was too scared to act.

💙

Patrick Smyth

December 6, 2025 AT 06:38Did you know that the CDC’s Heat & Health Tracker was funded by Soros? And that the "harm reduction" movement is just a front for drug legalization? This isn’t about saving lives-it’s about eroding moral boundaries under the guise of compassion. People are dying because they’re weak, not because the heat is too hot.

And why are we giving out cooling towels to addicts? Shouldn’t we be giving them job training? Or therapy? Or discipline? This is enabling. It’s not helping.

It’s sad. It’s tragic. But it’s not a climate crisis. It’s a character crisis.

Linda Migdal

December 7, 2025 AT 11:15Let’s be clear: this is what happens when you let open borders and socialist policies destroy the American work ethic. Why are we spending money on cooling centers for drug users when our own veterans are sleeping in their cars? This is why America is falling apart.

Stop coddling criminals. Stop funding leftist NGOs. Build more prisons, not more fans.

And for God’s sake, stop letting foreigners tell us how to run our public health system.

Tommy Walton

December 7, 2025 AT 15:55Heat + drugs = existential collapse. We’re all just atoms in a thermodynamic nightmare.

Meanwhile, my air conditioner hums like a lullaby. 🌬️✨

But what if the real overdose is capitalism? Just saying.

Also, I’m reading Baudrillard right now. He predicted this. 😌

James Steele

December 9, 2025 AT 12:07The ontological dissonance here is fascinating. The article weaponizes epidemiological data to normalize deviant behavior under the banner of harm reduction-yet fails to interrogate the epistemic frameworks that produce such behavior in the first place.

Is hydration a cure, or merely a palliative for systemic abandonment? Are we treating physiology-or merely performing virtue signaling?

Also, the phrase "people who use drugs" is itself a linguistic euphemism designed to sanitize the pathology of addiction. We must speak plainly: these are people in crisis. Not victims. Not statistics. People.

And yes-I carry naloxone. But I also carry Nietzsche. And I’m not ashamed to say it.

Louise Girvan

December 10, 2025 AT 11:54Wait. Wait. WAIT. The CDC? The same CDC that lied about masks? That pushed ivermectin as a joke? And now you want me to believe their "Heat & Health Tracker"? This is all a psyop. Heatwaves are engineered. The "overdose spike" is a distraction. They’re using climate fear to push surveillance tech and mandatory drug registries. You think they don’t track your water intake? Your location? Your pharmacy records?

They’re coming for your naloxone next.

And don’t you DARE tell me I’m paranoid. I’ve seen the documents.

soorya Raju

December 10, 2025 AT 12:57India has heatwaves too. But we don’t have "cooling centers" for drug users. We have chai stalls. And family. And community. You think a man dying alone in a US alley is the problem? No. The problem is you lost your soul. You don’t know your neighbor. You don’t know your brother. You pay someone to "check on" people like they’re robots.

Fix the heart, not the fan.

Also, my cousin died in 2020 from heat + heroin. No one helped. But his mom cooked for everyone in the block. That’s how we survive.

Not with towels. With love.

Dennis Jesuyon Balogun

December 11, 2025 AT 12:37Let me speak plainly: this is not about heat. This is about the death of dignity. In Nigeria, when someone is struggling, we don’t give them electrolytes-we give them a seat at the table. We sit with them. We ask: "What happened?" Not "What are you on?"

Western harm reduction is clinical. African community care is sacred.

You can’t cool a body if the soul is burning.

And yes-I carry naloxone. But I also carry my brother’s name in my pocket. He died in 2017. I still talk to him. That’s my medicine.

Don’t treat people like patients. Treat them like kin.

Grant Hurley

December 12, 2025 AT 16:57Just got back from volunteering at the pop-up cooling station downtown. Gave out 40 water bottles, 12 electrolyte packs, and 3 naloxone kits. One guy just sat there, crying, and said, "I didn’t think anyone remembered I was still here."

So yeah. This stuff matters.

Also, if you’re reading this and you’re not sure what to do-just text someone. "Hey, you good?" costs nothing. Could save everything.

Also, I spilled coffee on my shirt. Again. 🤷♂️