When a generic drug hits the shelf, you might assume it’s just a cheaper copy of the brand-name version. But behind that simple label is a rigorous, science-backed process designed to prove it works exactly the same way in your body. That process is called a bioequivalence study. These aren’t just lab tests-they’re tightly controlled clinical trials involving real people, precise measurements, and strict statistical rules. If you’ve ever wondered how regulators ensure a generic pill does the same job as the expensive brand, here’s how it actually works.

Why Bioequivalence Studies Exist

Before 1984, every generic drug needed its own full clinical trial to prove safety and effectiveness. That meant long delays and high costs. The U.S. Hatch-Waxman Act changed that by allowing generic manufacturers to rely on the original drug’s safety data-if they could prove their version delivered the same amount of active ingredient into the bloodstream at the same speed. That’s bioequivalence: not just the same chemical, but the same performance in the body. The same logic applies globally. The European Medicines Agency (EMA), Health Canada, Japan’s PMDA, and others all require bioequivalence data before approving a generic. The goal? Safe, affordable alternatives without compromising outcomes. According to the FDA, generic drugs saved the U.S. healthcare system over $1.6 trillion between 2010 and 2019. That’s only possible because these studies work.The Gold Standard: Crossover Design

Most bioequivalence studies use a two-period, two-sequence crossover design. That means 24 to 32 healthy volunteers (sometimes up to 100, depending on the drug) take both the generic (test) and brand-name (reference) versions-just not at the same time. Here’s how it breaks down:- Half the group takes the generic first, then the brand after a break.

- The other half takes the brand first, then the generic.

How Blood Samples Are Taken

After each dose, volunteers give blood samples at specific times. It’s not random. There’s a strict schedule to capture the full story of how the drug moves through the body. Samples are taken at:- Before dosing (baseline)

- Just before the peak concentration (Cmax)

- At the peak

- Two points after the peak

- Three or more points during elimination

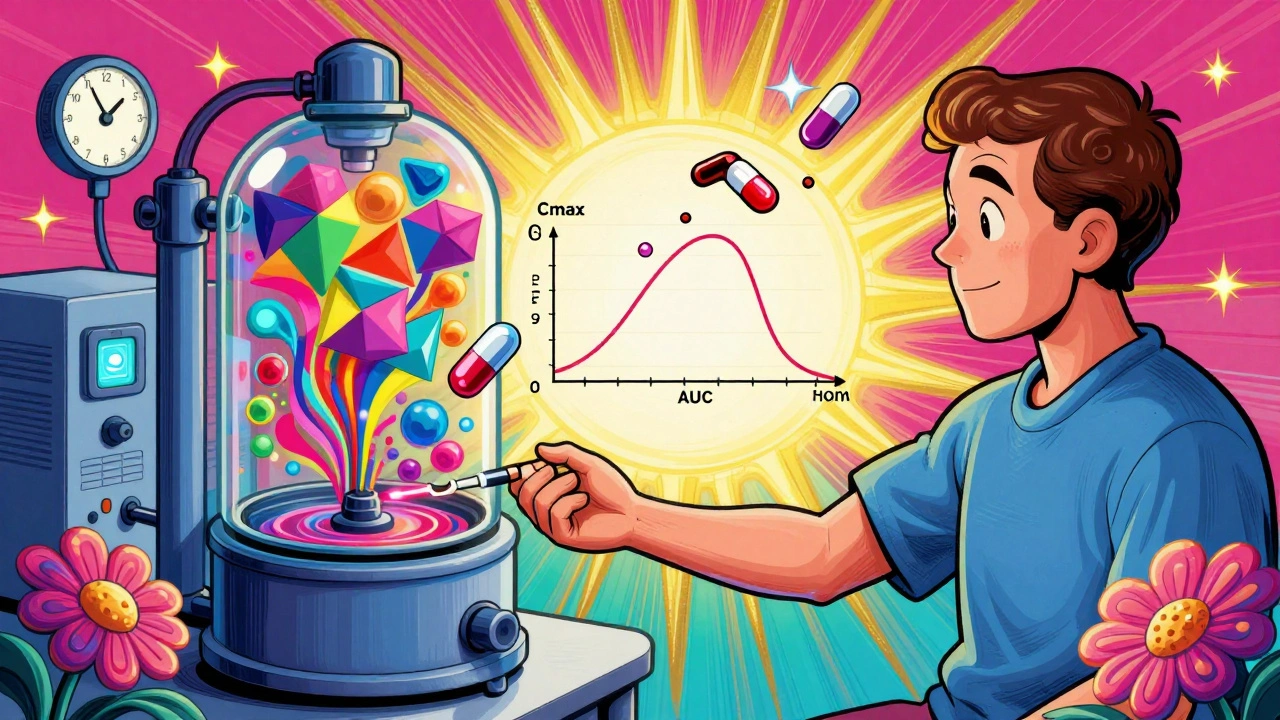

What’s Measured: Cmax and AUC

Two numbers decide whether the generic passes or fails:- Cmax: The highest concentration of the drug in the blood. This tells you how fast the drug gets absorbed.

- AUC(0-t): The total exposure over time-from when the drug enters the bloodstream until the last measurable point.

The Pass/Fail Rule: 80%-125%

Here’s the universal rule: for both Cmax and AUC, the 90% confidence interval of the geometric mean ratio (test/reference) must fall between 80.00% and 125.00%. That means the generic’s absorption can’t be more than 25% higher or 20% lower than the brand. This range was chosen because it reflects clinically insignificant differences-studies show patients don’t notice changes within this window. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-like warfarin, lithium, or phenytoin-the rules tighten to 90.00%-111.11%. Even small differences here could cause toxicity or treatment failure.What Happens When the Drug Is Highly Variable?

Some drugs-like certain statins or antiepileptics-show huge differences in how people absorb them, even when taking the same dose. That’s called high within-subject variability (CV > 30%). Standard crossover designs don’t work well here. The FDA allows reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE), which adjusts the acceptance range based on how variable the reference drug is. The EMA requires a four-period replicate design, where each subject takes both products twice. This gives more data to separate true differences from random noise. For example, a study on a highly variable drug might need 50-100 subjects instead of 24. These designs are more expensive and complex, but they’re necessary. Without them, many effective generics would never get approved.When Crossover Isn’t Possible

Not all drugs can be studied this way. If a drug has a half-life longer than two weeks, waiting five half-lives could take months. That’s impractical-and unethical-to ask volunteers to wait. In those cases, a parallel study is used: two separate groups, one gets the generic, the other the brand. No crossover. But this requires more people (often 100+) because you can’t compare individuals to themselves. For extended-release tablets or patches, multiple-dose studies are used. Instead of one dose, volunteers take the drug daily for several days to reach steady state, then blood samples are taken over time. Some drugs, like topical creams or inhalers, don’t enter the bloodstream in meaningful amounts. For those, regulators require pharmacodynamic or clinical endpoint studies. For example, a generic asthma inhaler might be tested by measuring lung function changes instead of blood levels.

What Makes a Study Fail?

The FDA’s 2022 Bioequivalence Study Tips document lists the top reasons studies fail:- 45%: Inadequate washout periods

- 30%: Poor sampling schedule (missing key time points)

- 25%: Statistical errors (wrong model, improper transformation)

- Using a reference product from the wrong batch (must be from the same lot used in original approval)

- Test product not made at commercial scale (must be ≥1/10 of production size or 100,000 units)

- Dissolution profiles don’t match across pH levels (f2 similarity factor must be >50)

How Long Does It Take?

A typical bioequivalence study takes 6-12 months from start to finish:- Protocol development: 2-3 months

- Regulatory submission and approval: 1-2 months

- Recruitment and dosing: 1-3 months

- Sample analysis: 1-2 months

- Statistical analysis and report: 1-2 months

- Regulatory review: 8-12 months (FDA median is 10.2 months)

What’s Changing in Bioequivalence

The field is evolving. Three big trends are shaping the future:- Modeling and simulation: Using computer models (PBPK) to predict how a drug behaves in different people. The FDA saw a 35% increase in these applications since 2020.

- BCS-based biowaivers: For drugs that dissolve easily and are highly absorbable (BCS Class I), regulators now allow waivers-no human study needed. In 2022, 27% of approvals used this route.

- Complex products: Inhalers, injectables, and topical gels are harder to replicate. New guidance is being developed to handle these, with GlobalData predicting 12.5% annual growth in studies for these products through 2027.

Final Thought: It’s Not Magic, It’s Math

Bioequivalence isn’t about proving a generic is “good enough.” It’s about proving it’s identical in performance. Every sample, every time point, every statistical calculation is designed to answer one question: Does this pill work the same way in your body as the brand? And the answer, for over 95% of approved generics, is yes. That’s why millions of people safely switch to generics every day-because the science behind it is solid, repeatable, and rigorously enforced.What is the main goal of a bioequivalence study?

The main goal is to prove that a generic drug delivers the same amount of active ingredient into the bloodstream at the same rate as the brand-name drug. This ensures it will have the same therapeutic effect without requiring new clinical trials.

How many people are usually in a bioequivalence study?

Most studies use 24 to 32 healthy volunteers. For highly variable drugs, studies may include 50 to 100 participants. Parallel studies, used for drugs with very long half-lives, may require even more.

Why is the 80%-125% range used for approval?

This range was established based on decades of clinical data showing that differences within this window don’t lead to noticeable changes in effectiveness or safety for most drugs. For narrow therapeutic index drugs, the range is tighter (90%-111.11%) to prevent risks.

Can a generic drug be approved without a human study?

Yes, for certain drugs classified as BCS Class I-those that dissolve easily and are highly absorbed-regulators may grant a biowaiver. This means only dissolution testing in the lab is required, not a human study.

What happens if a bioequivalence study fails?

The manufacturer must revise the formulation, improve the manufacturing process, or adjust the study design and resubmit. Common fixes include changing excipients, adjusting particle size, or running a replicate study for highly variable drugs. Failure often costs hundreds of thousands of dollars and delays market entry by months.

Tim Tinh

December 7, 2025 AT 16:36Philippa Barraclough

December 9, 2025 AT 01:41Raja Herbal

December 9, 2025 AT 09:36Jennifer Blandford

December 10, 2025 AT 12:14Lola Bchoudi

December 12, 2025 AT 03:14Michael Robinson

December 13, 2025 AT 15:49Olivia Portier

December 14, 2025 AT 21:30Noah Raines

December 15, 2025 AT 02:58Delaine Kiara

December 15, 2025 AT 05:03Tiffany Sowby

December 15, 2025 AT 22:28Asset Finance Komrade

December 17, 2025 AT 10:06Andrea Petrov

December 19, 2025 AT 02:10Suzanne Johnston

December 19, 2025 AT 22:04Stacy Tolbert

December 20, 2025 AT 09:57